When I first heard of grafted tomato plants, I thought: Grafting? Of annuals? Really? Grafting woody perennials, yes. The time, attention and effort required to produce a successful graft rewards us with years of fruit (trees) and/or beauty (think: roses). But all that work for the tender stems of tomato plants that only last a season? Yet grafted tomatoes, watermelon, cucumber, eggplant, and peppers are catching on worldwide — and for good reason.

When I first heard of grafted tomato plants, I thought: Grafting? Of annuals? Really? Grafting woody perennials, yes. The time, attention and effort required to produce a successful graft rewards us with years of fruit (trees) and/or beauty (think: roses). But all that work for the tender stems of tomato plants that only last a season? Yet grafted tomatoes, watermelon, cucumber, eggplant, and peppers are catching on worldwide — and for good reason.

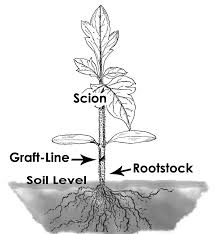

Grafting joins two plants of the same species but different varieties to create one plant. It’s designed to be a marriage of strengths – usually disease resistant roots (stock) wedded to a top cutting (scion) of a less disease-resistant but more appealing variety, for example vigorous Maxifort tomato root stock joined to the scion of luscious heirloom Tangerine tomatoes.

The process of grafting annual vegetable plants is theoretically simple. Take a plant with a strong rootstock, slice off its green top at an angle then slice through the stem of the desired top-growth plant (scion) cutting off its roots. Mate the sliced ends of the two plants and clip them together until the slice heals.

“The plant can begin to draw nutrients within 10 seconds,” says Peter Zuck, vegetable product manager at Johnny’s Selected Seeds in Winslow, ME, which sells grafted plants, “but the after care of the newly joined seedling is critical.”

As soon as the graft is made, plants must be kept at just the right temperature (70-74F) and humidity (80%-90%) and remain in low light to prevent top growth while the graft heals completely.

“Some people incorrectly think of it as similar to genetic engineering,” says John Bagnasco, managing partner at SuperNaturals Grafted Vegetables in Vista, CA, “but it’s not at all.”

Grafting has been a horticultural practice for centuries. The Bible mentions grafting olive trees in the book of Romans. The Chinese grafted the strong roots of wild tree peonies to their favorite cultivated stems in the 9th century.* But grafted annual vegetables and fruits are a relatively recent addition to the horticultural pantheon.

Grafting has been a horticultural practice for centuries. The Bible mentions grafting olive trees in the book of Romans. The Chinese grafted the strong roots of wild tree peonies to their favorite cultivated stems in the 9th century.* But grafted annual vegetables and fruits are a relatively recent addition to the horticultural pantheon.

“The Japanese began grafting them about thirty years ago,” says Bagnasco, who notes that Japan struggles with depleted, disease-prone, and challenging soils. “They have to graft to get

them to grow.”

Additionally, the 1997 Kyoto Protocols, which outlawed methol bromide used to control soil-borne fungal, bacterial and viral diseases, prompted an upsurge in the use of grafted annuals among its 197 signers, who needed an effective alternative to the pesticide.

“Almost 100% of the watermelons grown in Mexico are grafted now,” says Zuck.

In 2011, it was estimated that 1 billion grafted fruiting annuals were sold worldwide. In 2015, the number was 1.5 billion.

“Most were watermelon plants and most were sold in China,” says Bragnasco.

In addition to disease-resistance, the grafted plants tend to stand up to the kinds of climatic and regional stressors — soil salinity, temperature extremes, short seasons, and lower light — that can doom a vegetable garden, especially that succulent emblem of summer: tomatoes.

“Tomatoes don’t care for the broiling hot weather we have in summers around here,” says John Campbell of Annapolis, MD. Campbell has been growing grafted tomatoes in his home garden for ten years. “If the weather stays above 90 degrees for more than five days, they slow up on production. What I have found is that the grafted tomatoes suffer through this rotten summer weather with no problems, and I have not had any problems with disease.”

In addition to withstanding stressors, grafted vegetable plants can produce well despite less than optimal light. Most vegetables require six to eight hours of direct sunlight a day to fruit well.

“I had a small lot in Belfast [ME] with mature trees,” says Zuck. The tomatoes got about five hours of direct sun coupled with dappled sunlight and shade the rest of the day. “I found that the grafted plants helped me overcome that. They were much bigger and more productive than the non-grafted plants.”

“The plants produce anywhere from twice to three times the fruit, and they are exceedingly hardy,” says Campbell.

Another advantage for the home gardener with limited space is that grafting bypasses the need to rotate crops, a common practice used to avoid recurring soil-borne problems. Although grafted vegetable plants are obviously more expensive than non-grafted, for many home gardeners it’s worth it.

* An Illustrated History of Gardening, by Anthony Huxley, Lyons Press, 1978.